In The Hills of the Dead Howard returns to negative stereotypes for his black characters except for one; a small girl which he declares is:

[A] much higher type than the thick-lipped, bestial West Coast negroes to whom Kane had been used. She was slim and finely formed, of a deep brown hue rather than ebony; her nose was straight and thin-bridged, her lips were not too thick. Somewhere in her blood there was a strong Berber strain. (Del Rey edition; The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane, p. 230-31).There are several things going on in this passage that the casual reader could too easily overlook. First, it is quite obvious that Howard has done his research and done it well. He describes the indigenous Berber people of North Africa who lived west of the Nile river. Second he describes this type as a higher type. What does he mean by "higher type"? Is he merely trying to demean the "lower type" by calling the Berbers "higher?" Or is he pointing out diversity among various indigenous Africans? Third, his use of a small child is ingenious because it practically demands sympathy. What better way to gain sympathy for a dark skinned person than to make her a girl and a child at that? All these factors, especially the understanding of diversity between people and Howard's use of a small female child is a clever and subtle way to get his reader to slowly empathize and understand characters who would otherwise be thought of as racially sub-standard.

What is more, and this is crucial, N'Longa reappears at the beginning of The Hills of the Dead. Only this time N'Longa gives Solomon an important gift—the famous Staff that is older than the world. Even though Kane is hesitant to take the staff, an exchange like this between a black person and a white person is, at best, extremely unusual given the decade in which the story was published. It can certainly be viewed as a positive action between two races who are otherwise always at odds with one another. Moreover, the staff is an instrument of help, and is intended to help Solomon in his travels. It's almost as if this is a type of peace offering between two races.

Now we come to Wings in the Night. In this story Howard is in rare but extraordinary form. He begins the story with this opening sentence:

Solomon Kane leaned on his strangely carved staff and gazed in scowling perplexity at the mystery which spread silently before him. (Del Rey edition; The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane, p. 275)The first thing Howard mentions is the staff given to Solomon Kane by N'Longa. A staff that will later be used to help a tribe of natives in Bogonda. As the story progresses, Solomon Kane is chased down by a group of flying human-like beasts (we later find out are harpies). Kane kills one of the beasts but is injured. He is brought unconscious to a tribe of natives. These natives nurse Kane back to health.

The interesting thing about the natives from Wings in the Night is that they are not like any other natives Howard has written. First, they have a more appropriate manner of speech (as crazy as that sounds it is an important detail). Second, they are more intelligent than any other Kane has encountered. Third, this area, called Boganda, has never encountered a white man. Fourth, because they have never seen a white man and they witness Kane kill one of the harpies (what they call an akaana) they assume Kane is a god. Kane corrects them and declares, "I am no god. . . . but a man like yourself, albeit my skin be white."

Two interesting things occur in Kane's response. First, Kane claims that he is equal with these men—"I am a man like yourself." Second, to correct their claim of deity toward Kane, he explains—"Albeit my skin be white." Howard eliminates any sense of superiority and uses the fact that these natives have never seen a white man to defeat the idea of deifying one. The combination of color and the fact that Kane has killed a beast that has given these people grief for so long is why they mistake him as a god. But Howard levels the playing field, so to speak, and has Kane declare that he is their equal. This, I might add, is a pretty liberal thing to write in Howard's day. But, there are more interesting things to come in the story. (To be continued).

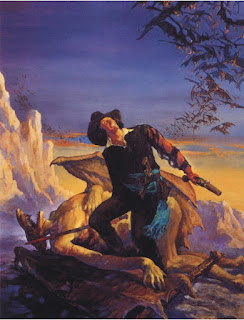

[The illustration used in this post is Gary Gianni's and comes from the Del Rey edition of The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane.]

Great post, I look forward to the rest.

ReplyDeleteI agree it is Howard's outlook and attitudes that birth such an excellent character.

Hey, David. I see you got your computer working. That's good. Thanks for the kind remarks. I've been working my tail end off at my job and have not been able to devote as much time to this blog as I'd like, but hopefully that will change in the near future. I'll post the follow up asap. Cheers.

ReplyDelete