Today, it is easy to know about the friendship of H. P.

Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. Their correspondence is collected in the

two-volume set A Means to Freedom (with

some partial drafts in the Collected

Letters of Robert E. Howard - Index and Addenda), and these letters provide

fans and scholars with considerable insight into both men, their travels,

philosophies, and arguments written out in their own words. Taken as a whole,

the thousand pages of AMTF represents

a literary achievement at least the equal to any of their fiction. Yet it is not

quite the whole story.

|

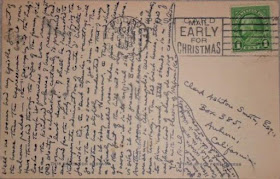

| A postcard from H.P. Lovecraft to Clark Ashton Smith, ca December 1933. |

Lovecraft epistles (both letters and postcards) numbered in the

tens of thousands. Several mentioned Robert E. Howard, or his work. Ranging

from brief snippets to full pages of text, these references to and about Howard

informed Lovecraft’s audience and helped shape their vision of the man from

Cross Plains. Since none except E. Hoffmann Price met Two-Gun Bob in person,

and relatively few corresponded with him on their own, these comments from

Lovecraft likely formed the only picture they had of “Brother Conan,” outside

of his fiction.

The earliest references to Howard in Lovecraft’s published

letters date before the two men began writing to one another, noting the “The

Skull in the Stars” (ES1.176), “The Shadow Kingdom” (ES1.200), and “Skull-Face” (ES1.243)

as stand out pieces at Weird Tales,

with Lovecraft praising Howard to editor Farnsworth Wright (LA8.22). Lovecraft later recalled the

beginning of their correspondence:

I first became conscious of him as a

coming leader just a decade ago—when (on a bench in Prospect Park, Brooklyn) I

read Wolfshead. I had read his two

previous short tales with pleasure, but without especially noting the author.

Now—in ‘26—I saw that W.T. had landed

a new big-timer of the CAS and EHP calibre. Nor was I ever disappointed in the

zestful and vigorous newcomer. He made good—and how! Much as I admired him, I

had no correspondence with him till 1930—for I was never a guy to butt in on

people. In that year he read the reprint of my Rats in the Walls and instantly spotted the bit of harmless fakery

whereby I lifted a Celtic phrase (for use as an atavistic exclamation) from a

footnote to an old classic—The Sin-Eater,

by Fiona McLeod (William Sharp). He didn’t realise the source of the phrase,

but his sharp eye for Celtic antiquities told him it didn’t quite fit—being a Gaelic (not Cymric) expression assigned to a South British locale. I myself

don’t know a word of any Celtic tongue, and never fancied anybody could spot

the incongruity. Too charitable to suspect me of ignorant appropriation, he

came to the conclusion that I followed a now-discredited theory whereby the

Gaels were supposed to have preceded the Cymri in England—and wrote Satrap

Pharnabazus a long and scholarly letter on the subject. Farny passed this on to

me—and I couldn’t rest easy until I had set the author right. Hence I dropped

REH a line confessing my ignorance and telling him that I had merely picked a

phrase with the right meaning from a note to a Scottish story while perfectly

well aware that the language of Celtic South-Britain was really somewhat

different. I could not resist adding some incidental praise of his work—echoing

remarks previously made in the Eyrie. Well—he replied at length, and the result

was a bulky correspondence which throve from that day to this. I value that

correspondence as one of the most broadening and sharpening influences in my

later years. (SL5.277, cf. SL5.181)

Lovecraft warmed quickly to his new pen-pal, and by November

1930 told Frank Belknap Long he considered Howard a permanent correspondent,

whose letters were “heavy” and arrived at “moderate” intervals. (SL3.205) By the fall of 1931 Howard was

one of the gang, spoken of as part of the group of notable Weird Tales authors (SL3.416),

and on the circulation list for drafts and carbons of stories within the group

(CL2.273; ES2.626, 719; OFF 8, 10; LRBO 69; MTS 317, 318, 364; SL4.331),

and through Lovecraft Robert E. Howard came into contact with future

correspondents such as R. H. Barlow (OFF 10),

August Derleth (ES1.384), Donald

Wandrei (MTS 294), Clark Ashton Smith

(AMTF2.619), and Carl Jacobi (SL4.25). Howard was, in short, “one of

the family.” (LRBO 143)

By April 1932, Lovecraft had begun to refer to him his

now-famous nicknames—Bran Mak Morn (ES2.471),

REH (ES2.477), “our Master of

Massacre” and Conan the Reaver (ES2.523), Two-Gun Bob (SL4.119), Sagebrush Bob (SL4.180),

“the Terror of the Plains” (LRBO 46),

Brother Conan (SL5.271), and Longhorn

(SL4.181)—of these, “Two-Gun” was by

far the most common to appear in Lovecraft’s letters, and still has some stick,

as can be seen in Jim and Ruth Keegan’s The

Adventures of Two-Gun Bob. It’s interesting that Clark Ashton Smith

preferred to nickname REH “Conan” or “the Cimmerian Monarch” in his own

letters. (SLCAS 239, 245)

In 1932, after they had been corresponding for about a little

over two years, Lovecraft offers his first mini-biography of Howard:

REH was born in Texas in 1906, of old

Southwestern & Southern stock. The Howard line came from England to Georgia

in 1735. The Ervin line has produced men of high standing &

ability—Confederate officers, planters, Texas pioneers. A large part of REH’s

blood is Irish, & he takes great pride in his knowledge of Celtic history

& antiquities. He lives with his parents in a village from which pioneer

violence has not yet fully departed. His father is a physician of high

standing, & great courage & resourcefulness, who once fought a knife

duel with one hand tied behind his back. REH is a typical primitive throwback

in emotions—idealising barbaric & pioneer life. He hated school—yet loved

books so much that he used to force open a window of the school library in the

summer, when it was closed, in order to take & return things he wanted to

read. He is today a really profound authority—on Southwestern history &

folklore—as well as on ancient history. He began to write stories very young,

but takes very little pride in them—saying he’d rather be a good prize-fighter

than a good novelist. Being brought up in a rough town, he came to accept rough

ways as a matter of course. He has been through dozens of fights, with &

without weapons, & has served as an amateur boxer. I think he was once

connected in some way with a travelling carnival. I judge he was rather a

roving character in his teens—away from home a good deal. He says he feels most

at home among rough workmen, & has passionately strong sympathies for the

under-dog despite a personally aristocratic ancestry. He is very bitter &

cynical in temperament—but kindly & sympathetic at the same time. Extremely

brave & conscientious. At one time during his teens he worked at a drug

store soda fountain. He has seen a good deal of the rough life of oil boom

towns, & hotly resents the way large eastern corporations exploit Texas.

When he says his life is ‘tame & uneventful’, he is thinking only of

Western standards. Actually, he sees a vast amount of violence. He sympathises

greatly with outlaws, & is really a fanatic on the subject of alleged

police persecutions—unjust arrests, 3d degree, &c. His fetishes are

strength, civility, justice, & freedom. Everything civilised, soft,

effeminate, or orderly he hates with astonishing venom. In ancient history he

detests Rome as strongly as I revere it. He travels occasionally in Texas &

the S. W.—has seen the Carlsbad Caverns & sometimes spends the winter in

San Antonio. Has never been east of New Orleans. First stories published in W.T. in 1925 or 6. A poet of savagely

great power. So fond of his Celtic heritage that he has Gaelicised his middle

name Ervin into Eiarbihan—as the fanatics in Ireland nowadays Gaelicise theirs.

Tastes in literature somewhat uneven—despises all modern subtlety & likes

books about simple characters & violent events. Would rather be a Celtic

barbarian of 100 or 200 B. C. than a civilised modern. (SL5.107-108, cf. ES2.523-524)

|

| Two-Gun Bob |

This biography, which is fairly typical of those in other

letters written by Lovecraft, is not purposefully deceitful but amid the facts

contains a fair amount of hyperbole and one or two errors—such as the line

about Howard traveling with carnivals, which arose out of Lovecraft

misremembering or misunderstanding an anecdote of when REH, at the age of 14,

worked for a little while at a carnival. (AMTF1.348-349;

CL2.404-405) None of the statements

are outright fictions, however, and all of them can be traced directly back to

one or more passages in Howard’s lengthy letters to Lovecraft.

The length and bulk of Howard’s letters was a subject worthy of

mentioning to Lovecraft’s correspondents—few of whom could match Lovecraft

himself in the length of their epistles—and he described them as “enormous” (OFF 154), “voluminous” (SL5.107). He wrote August Derleth that

they were “18 or 20 closely typed pages each time” (ES2.523), remarked to Donald Wandrei how he received “a 22-page

(closely typed) argumentative epistle from Two-Gun Bob, the Terror of the

Plains.” (MTS 338), and told Willis

Conover “20 to 25 pages closely typed was not unusual for Robert E. Howard.” (LRBO 394)—though the actual length of

their correspondence varied considerably, such lengthy missives were not

uncommon. As to the content of these lengthy letters, Lovecraft was effusive with

praise:

Some of the long argumentative &

descriptive letters of our group really approach literature—the most remarkable

ones coming from Robert E. Howard, whose reminiscences & historical

sketches of his native Texas country are literature in the truest sense of the

word, far more so than any save the very best of his stories. (OFF 56)

The Rhode Islander expressed his “admiration for the author’s

vivid letters on Texas history & tradition” (ES1.384) and talked about Howard’s “marvellous outbursts of historic

retrospection & geographical description” (LRBO 257, cf. SL5.215)

and described them as like essays “with their fragments of bygone strife, their

exaltations of barbarick life, & their tirades against civilisation” (LJFM 389, cf. LRS 82)—indeed, Lovecraft remarked on Howard’s letters much as

others have remarked on Lovecraft’s letters. The “extended arguments in favour

of barbarism as opposed to civilisation” (LRBO

394) formed part of the long running argument that the two men engaged in,

of which Lovecraft’s other correspondents only received fragments—and those

from Lovecraft’s point of view:

The big issue was civilisation versus

barbarism. I claim the barbarian of superior race represents a regrettable waste of biological capacity; since his

energies are chained to a mere struggle for physical survival, while his

intellect and imagination are restricted to a very narrow range of functioning

which leaves their richest and most pleasurable potentialities absolutely

undeveloped. I fully concede the existence of many admirable qualities in

barbarian life, as well as the fact that civilisation brings certain inevitable

losses to offset the gains; but must insist that on the whole the boons of

civilisation add up to a vastly greater total than do the boons of barbarism.

No system of life can be said to be normal or desirable if it leaves unused and

undeveloped the very highest qualities which aeon-long evolution has brought to

a species. [...] It almost puzzles me that Two-Gun is able to maintain seriously

the position he claims to maintain—yet I suppose the west Texas environment

counts for much. With his intense rooting in his native soil, he feels himself

called upon to idealise all those tendencies in which the southwest differs

from the rest of European civilisation. (SL4.180-181)

|

| A Means to Freedom: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft & Robert E. Howard Vols. 1-2 |

Getting Howard’s side of the argument through Lovecraft gave a

stilted view of the Texan’s true position—as the editors of A Means to Freedom noted, the two had a

tendency to talk past each other. (AMTF1.9)

Descriptions of Howard’s character are thus often overblown from the content of

his letters to Lovecraft:

He sympathises greatly with outlaws,

& is really a fanatic on the subject of alleged police persecutions—unjust

arrests, 3d degree, &c. His fetishes are strength, civility, justice, &

freedom. Everything civilised, soft, effeminate, or orderly he hates with

astonishing venom. In ancient history he detests Rome as strongly as I revere

it. (SL5.108)

He has an odd, primitive

philosophy—hating all civilisation (like Lord Monboddo & other devotees of

the “noble savage” in my own 18th century) & regarding the barbarism of the

pre-Roman Gauls as the ideal form of life. (LAG

193-194)

He is an old-time Texan steeped in the

virile & sanguinary lore of his native region, & writes of his local

traditions with a force, sincerity, & genuinely poetic power which would

surprise those who know only his more or less conventional contributions to the

magazines. His letters form a veritable epic of primitive emotions & deeds

in a grim & rugged setting—the last free play of the old Aryan tribal &

combative instincts of which Homer & the Eddas & Sagas sing. (SL4.25)

This issue was exacerbated by both Howard’s Texan tall-tales

and Lovecraft’s either gullibility in believing them or gentle fun in

exaggerating them--as shown in a letter to Bernard Austin Dwyer:

I never realised, until my

correspondence with Longhorn just how much of the primitive and sanguinary

still lingers in Texan life and psychology It was my idea that all that stuff

vanished in the 1890s, and that the “Wild West” of today was a mere convention

of cheap fictioneers. Now I see my mistake—a mistake which I think the average

Easterner shares. Evidently in Texas mothers send their precious 3-year-olds to

kindergarten with six-shooters on their hips, and with instructions to plug the

teacher quickly if he draws a gun first! (SL4.180-181)

If Lovecraft misrepresented Howard’s arguments or presented a

caricature of his thoughts and personality, he was always staunch in his

conviction of his talent as a writer. “But if you were to see his letters [...]

you would perceive a remarkable character as different from the perpetrator of

Conan the Reaver [...]” (ES2.523)

“His letters have a greater literary value than his tales.” (LRBO 23) “His long letters shewed what

was in him—& what would have come out some time.” (ES2.739)

Works Cited

AMTF A

Means to Freedom: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard (2

vols.)

CL Collected

Letters of Robert E. Howard (3 vols. + Index and Addenda)

ES Essential

Solitude: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and August Derleth (2 vols.)

LA Lovecraft

Annual (9 vols.)

LAG Letters

to Alfred Galpin

LE H.

P. Lovecraft in “The Eyrie”

LET Letters

to Elizabeth Toldridge and Anne Tillery Renshaw

LJFM Letters

to James F. Morton

LHK Letters

to Henry Kuttner

LRBO Letters

to Robert Bloch and Others

LRS Letters

to Richard F. Searight

MTS Mysteries

of Time and Spirit: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Donald Wandrei

OFF O

Fortunate Floridian: H. P. Lovecraft’s Letters to R. H. Barlow

SL Selected

Letters of H. P. Lovecraft (5 vols.)

SLCAS Selected

Letters of Clark Ashton Smith

SR Sable

Revery

UL H.

P. Lovecraft: Uncollected Letters

WD Fritz

Leiber and H. P. Lovecraft: Writers of the Dark

About Bobby Derie

Bobby Derie is the author

of Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014, Hippocampus Press) and Collected Letters of Robert E.

Howard - Index and Addenda (2015, Robert E. Howard Foundation Press). Researching those books involved buying many

volumes of letters, so he figured he ought to get some use out of them.

Just now discovered your wonderful site. I look forward to the second installment of this article.

ReplyDeleteI have been reading my way through a collection of H.P. Lovecraft's letters circa 1932-1934, which include a number sent to Howard. I've wondered what Howard's contribution to the the dialogue had been, given Lovecraft's frequently lengthy and detailed response.

Do you recommend a vendor for "A Means to Freedom" or the three volume "Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard"?

Thanks.

A MEANS TO FREEDOM (2 vols.) and THE COLLECTED LETTERS OF ROBERT E. HOWARD (3 vols. + Index and Addenda) are both excellent collections. If you're interested specifically in the Howard/Lovecraft correspondence, I'd go with AMTF - while the Collected Letters has all of REH's side of the correspondence, Lovecraft's portion is not fully published anywhere else, not even in the SELECTED LETTERS OF H. P. LOVECRAFT (5 vols. + Index).

ReplyDeleteHowever, be aware that AMTF is out of print with the price increasing, and the Collected Letters are nearly out of print with a full set being scarce and expensive.

Hey Sean, thank you for the nice comment about my blog. As Bobby so aptly described above, AMTF is no longer in print - you might try Abebooks.com, they may have a set at a reasonable price. Most of the used vendors at Amazon are expensive with out of print titles (and unreliable on their condition descriptions), but you might try looking there too.

ReplyDeleteAs for the Collected Letters of REH, the REH Foundation sells the first two volumes of that set & The Index & Addenda here - (http://www.rehfoundation.org/category/merchandise/). However, the first volume is sold out. It would not surprise me - due to the growth of popular demand for these letters if they re-issue those in the future sometime - perhaps in paperback.

Glad you enjoy the site.

Cheers!

Todd