Pirates and Buccaneers, their exploits, adventures, and duels, make a strong mark on many of Robert E. Howard’s stories. The sources for these inspirations are somewhat broad. There are nonfiction books about pirates, their history, their adventures and deaths that Howard read early in his life. Then there is the fiction Howard read that impacted his own stories with swashbuckling duels, high adventure, treasure hunts, and the like. All these pirate histories and fictional works played a pivotal role in Howard’s creation of various characters, especially his more famous Puritan duelist, Solomon Kane, and several Kane stories.

At an early age Howard discovered and became fascinated with pirates and buccaneers. This is evident in T. A. Burns’ essay for the 10 July 1936 issue of The Cross Plains Review where she explained that a young Howard (likely age 12 or 13 at the time) proudly introduced himself and his dog to her (during one of her frequent outings to read and enjoy the outdoors) and declared that someday he was going to write pirate stories. There are any number of resources for Howard’s interest in pirates. The most difficult to determine are the books he read prior to the age of 15. But by age 15 and beyond, Howard mentions several works that fueled his passion for pirate tales. Howard wrote a brief essay for his English Class No. 3 at Cross Plains High school dated February 7, 1922. A few weeks prior he had turned 16. In this essay, Howard mentions that when he was younger, he read a Captain Kidd biography and various fictions about the pirate. These works enamored him. Here are Howard’s exact words: “Reading his [Captain Kidd’s] biography and fiction based on his eventful life, caused me to determine at an early age, to lead a life of piracy on the high seas. Tales of Blackbeard and Morgan clinched my resolve.” [Howard, Back to School, 271]

Sometime later, Howard set aside his puerile notion of leading a pirate’s life after reading a different book. According to this same high school essay, the author’s name and the title of this other book escaped Howard’s memory. But he explained that this author “wrote an authentic book about piracy and by some means I secured it [. . .] and devoured it with avidity but was shocked to find that it contained a harrowing account of the deaths of Kidd, Blackbeard, and other noted gentlemen.” [Ibid.] Howard described, in his typical hyperbolic fashion and vivid detail, that the book contained a gruesome image of a known pirate, shortly after his execution, with a spike driven through his head. The contents and that illustration from the book caused Howard to reconsider his vocational desire of piracy on the high seas. It did not, however, deter his passion for pirate tales. In fact, it probably fueled it.

Howard began reading pirate tales from around the age of eight or earlier. One of the earliest works Howard experienced in the literary crafting of high adventure is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Apropos to Howard’s interest or maybe even the cause, Stevenson’s tale is about buccaneers and buried treasure. What more could an impressionable boy desire than to be a buccaneer who uses a map to find buried treasure? Stevenson’s story ignited young imaginations around the globe. And that motif lasted for more than a century, first in fiction and later in films. Howard jumped on this creative bandwagon in multiple ways. In fact, his poem, “Flint’s Passing” is an homage to Stevenson’s story and characters, Captain Flint and Long John Silver. But what about that authentic account mentioned in Howard’s essay, that spurned his notion of living the pirate’s life? |

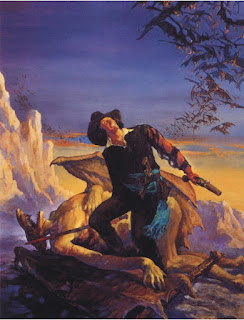

| Illustration by Pyle |

I came across another book that I thought might be a contender: Captain William Kidd And Others of the Pirates Or Buccaneers who Ravaged the Seas, the Islands, and the Continents of America Two Hundred Years Ago by John Stevens Cabot Abbott (1876). The contents of Abbott’s book is close to what Howard described in his essay, “it contained a harrowing account of the deaths of Kidd, Blackbeard, and other noted gentlemen.” [Ibid.] Some of the illustrations where gruesome for their day, and this image was toward the back of the book but did not depict exactly what Howard described.

|

| Illustration from Abbott's Captain William Kidd |

While I was poring over pirate books, I began corresponding with Howard scholar Rusty Burke. I told Burke about my research for this article and he immediately turned a light switch on. He said he had done something similar some time ago and the best book he could find that fit Howard’s description was The Pirates Own Book: Authentic Narratives of the Most Celebrated Sea Robbers by Charles Ellms (1837). The contents matched and in the middle of the book is an image of the head of Benavides stuck on a pole (below).