In “The Eyrie” of the March 1924 issue of Weird Tales, H. P. Lovecraft wrote, “Popular authors do not and apparently cannot appreciate the fact that true art is obtainable only by rejecting normally and conventionality in toto, and approaching a theme purged utterly of any usual or preconceived point of view.”[1] A bold statement, to say the least, especially in a magazine whose byline is The Unique Magazine. But Lovecraft demanded his fiction to be unconventionally ‘other than,’ and as original as possible. For him, crafting a story was an art form. In this same letter, Lovecraft goes on to declare:

Wild and ‘different’ as they may consider their

quasi-weird products, it remains a fact that the bizarrerie is on the surface

alone; and that basically they reiterate the same old conventional values and

motives and perspectives. Good and evil, teleological illusion, sugary

sentiment, anthropocentric psychology—the usual superficial stock trade, and

all shot through with the eternal and inescapable commonplace.[2]

Had Lovecraft accepted the job as editor when J. C. Henneberger offered it to him back in 1924, he would have likely been a harsh editor, and the magazine would have taken a decidedly different path. Much of the fiction Edwin Baird and Farnsworth Wright accepted would have, no doubt, been rejected by Lovecraft. But alas, we were rewarded the benefit of Lovecraft the writer. There is no telling exactly which stories or authors Lovecraft was disparaging in this letter to Weird Tales’ editor at the time, Edwin Baird. They may have not been Weird Tales’ authors, though it is likely most were. Even so, Lovecraft is making a valid point regarding breaking away from conventional story writing, creating an original tale, thinking outside the box. At least his creative mind demanded as much. Something he also expected, or at least wanted other writers to do. Some of the readers of The Unique Magazine demanded the same, at least they demanded their stories weird, if not ‘original.’

|

| H. P. L |

So, in an effort to

promulgate something weird and original, Lovecraft made this suggestion: “Take

a werewolf story, for instance—who ever wrote one from the point of view of the

wolf, and sympathizing strongly with the devil to whom he has sold himself?”[3]

Those

of us who love the pulps and their writers (we all have our favorites, of

course), probably know that H. Warner Munn attempted to answer Lovecraft’s

request with, “The Werewolf of Ponkert,” Munn’s first published short story.

About Munn’s story, Farnsworth Wright claimed, “It was the popularity of Mr.

Quinn’s werewolf story[4] that led us to feature The Werewolf of Ponkert, by H. Warner

Munn, in last months’ issue.”[5] (italics is Wright’s) “The

Werewolf of Ponkert” was the cover story for the July 1925 issue of Weird Tales, the same issue in which Robert E.

Howard made his debut with “Spear and Fang.”

Lovecraft,

as far as I’ve been able to determine, never responded to Munn’s story in “The

Eyrie” of any of the subsequent Weird

Tales issues. It’s possible that when “The Werewolf of Ponkert” was first

published, Lovecraft did not put two and two together and notice that his March

1924 letter in “The Eyrie” was Munn’s inspiration. In fact, it may be that

Lovecraft never knew that fact until after he met Munn, and Munn confessed as

much. However, there is some evidence from Munn himself that Lovecraft may have

recognized Munn’s efforts on behalf of Lovecraft’s letter:

Thinking about the first-person idea tendered in Weird Tales, a tale formulated; I wrote it down, sending it to Weird Tales’ editor Farnsworth Wright, and he bought at [sic] for the usual price of a penny a word. I got a check for $65.00. Bingo! I was now a writer. And as a result of the tale, I received a congratulatory note from the man who had written the letter suggesting my story.[6]

Munn was 22 at the time

and up to that point he had only had a few poems published but no fiction.

Which means his first time at the proverbial home plate of short fiction

resulted in a cover story home-run. The “note” that Lovecraft wrote Munn, as

far as we know, no longer exists, so it is impossible to know if it was written

merely to congratulate Munn for writing a good cover story, or for using

Lovecraft’s idea from his March 1924 letter. Moreover, Munn does not further

elaborate on the contents of the note.

|

| Lovecraft and Cook |

It was W.

Paul Cook, a close friend of Munn’s, who alerted Munn about Lovecraft’s March 1924 Weird Tales. Cook, a jack-of-all trades,

was “a printer, an amateur writer, a book publisher, and several times

president of the Amateur Press Association.”[7] Shortly after Munn’s story

published in Weird Tales, Munn showed

Cook the note he received from Lovecraft. Because of Cook’s associations in

amateur journalism at the time, he was a friend of Lovecraft’s. So, Cook asked

Munn if he’d like to meet Lovecraft, an offer Munn quickly accepted. Munn

traveled with Cook from Athol Massachusetts (where he was born and raised) to

Providence, RI to visit Lovecraft. This trip took place almost two years after

Lovecraft’s congratulatory note to Munn, in the summer of 1927. Lovecraft

detailed the visit to Clark Ashton Smith in an August 2, 1927 letter:

My other guests were very welcome, too—Morton, Long

& his parents, Cook and Munn. Munn is a very promising youth of the blond,

muscular type. He will probably develop into a romancer rather than

fantaisiste, & thus have a better chance of professional success.[8]

Of course, Munn continued

writing weird fiction (mostly horror), and while not as successful nor as

prolific as Lovecraft, he did manage to write some very memorable stories that

are still being read today. Some of the more notable stories are from his

werewolf series called Tales of the

Werewolf Clan. From this initial meet and greet, a

lengthy friendship and continual correspondence ensued between the two writers,

along with more occasional trips between their home towns to see one another.

|

| Unknown October 1939 |

Munn was prone to write

more historical adventure and romance stories with traditional Gothic themes

such as werewolves and the like, something Lovecraft thought was mostly junk.[11] For instance, regarding

Munn’s story from the December 1930 Weird

Tales, “Tales of the Werewolf Clan: The Master Strikes,” Lovecraft

declared, “The trouble with Munn’s tale is that it subscribes too much to the

traditional of swashbuckling romance—the Stanley J. Weyman cloak & swordism

of 1900.”[12]

This was simply a literary tradition Lovecraft did not care for. But, it was

one in which Munn preferred and with which he managed some measure of success. Regardless

of Lovecraft’s preferences, he supported Munn’s efforts (at least to his face)

though he did confess to August Derleth about some issues he had with Munn’s Gothic tales:

Yes—Munn does get into arid and sterile regions when

he tries to hitch his romantic-adventure mood and technique to the domain of

the weird. He is drawing the poor Master out to such lengths that one cannot

keep track of the creature's nature and attributes—indeed, the impression is

that he merely retains the supernatural framework as a matter of duty—or

concession to Wright—whereas he really wants to write a straight historical

romance. But the kid's young, and we can well afford to give him time. Let him

get Ponkertian werewolves out of his system, and see what he can do with a fresh

start![13]

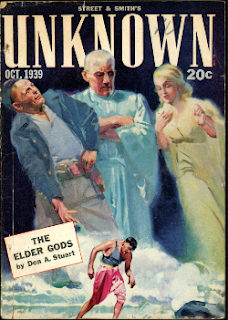

In between writing his Werewolf Clan stories, Munn

managed to create some lively strange tales such as “The City of Spiders” (1926),

“The Chain” (1928), “A Sprig of Rosemary,” (1933), and “Dreams May Come” (1939),

his first new market story published in the October 1939 Unknown magazine. Aside from the earliest two (which are well worth

reading), none surpassed the quality of the stories in his Werewolf Clan

series. The last thing Munn wrote, possibly due to marriage and family obligations,

was a four-part series that Weird Tales

published between the September to December 1939 issues titled, “King of the

World’s Edge.” In this series, Munn works within the historical context of

exploration and Roman history to weave a stunning tales of new world

discoveries, barbaric empires, and fish-monsters. It is a kind of sword &

sorcery story but in an actual historical context and setting which includes

monsters, magic, and swordplay, what’s not to like? The series, in a nut shell,

is about a document, written by Ventidius Varro, a British-Roman legionnaire.

It was discovered after a hurricane in the southern Florida Keys. The events in

the discovered document take place during the height of King Arthur’s reign,

but Arthur is defeated in battle, and this is the final days of Roman

occupation in Britain. Soldiers, along with Arthur and a mage named Myrdhinn,

are isolated and left to fight the invading Saxon marauders. At the point

Arthur is defeated, Myrdhinn and the remaining legionnaires set sail for a

place to hide and end up in the new world where they experience strange lands,

new people (tribes), and odd creatures. In this new world, they attempt to

create a new civilization but must first overcome certain adversities.

On January 14, 1930, Munn married Malvena Ruth Beaudoin. She

eventually accompanied her husband and Cook on various excursions to visit

Lovecraft and would host Lovecraft when he visited the Munns. To better

understand their conversations, Malvena read several of Lovecraft’s stories.

Munn declared that Malvena “found it difficult to understand some of his

stories, but when he visited us, he did make a conscious effort to speak simply

and easily.”[14]

About Lovecraft, Malvena once said: “He talks as though he had swallowed a

dictionary.”[15]

The Munns had their first child (John Warner) in 1931, and another (James

Edward) in 1936. With new responsibilities and an inability to publish enough

stories to support a growing family, Munn stepped away from writing for nearly

30 years and worked various conventional jobs. However, he continued to write and

publish for 9 years after he married, he also continued his friendship with

both Cook and Lovecraft.

At

one point, Cook gave Munn his entire library, which apparently was the envy of

Lovecraft, who admitted as much in a letter to R.H. Barlow:

Cook gave most of his library to H. Warner Munn. He

has virtually nothing now—except perhaps a few stray items up at his sister’s

in New Hampshire. Yes—it was full of fantastic stuff—the best library of the

sort I ever encountered. Munn, of course, now has the best collection.[16]

The loss of Cook’s

library to Munn was a progressive road to hardship and a nervous collapse

beginning with the death of his wife in 1930. Over the next few years, Cook

lost his job when the company closed due to the Great Depression. Cook

explains:

I suddenly found myself struck down

from a comfortable condition of life with an income of about $5000 to a grade

of no income and in debt about $1000. I have discarded everything; have given

away or thrown away everything, including my job, my real estate, my household

furnishings, and my library.[17]

|

| H. Warner Munn |

Cook retained a few

select volumes, and likely gave Munn his library for sake-keeping. Shortly

after 1934, Munn began to slowly ignore his correspondence, failing to respond

to letters, and Lovecraft became a bit frustrated by this. During this period, Lovecraft

once declared, “As for Munn, he’s the most notorious neglectful person in the

gang . . . his negligence amounting to a positive psychological defect.”

Lovecraft continues, “For example—Fantasy

Magazine wants to get a hold of the long & important article on popular

bizarre fiction which he wrote for Cook’s defunct Recluse, yet letters from its editor remain unanswered.”[18] Lovecraft likely heard

about this from Cook, who apparently was also unable to get in touch with Munn at this time. It is

uncertain why Munn was non-responsive during this period. He even took a break

from publishing between 1933 and 1939. By July of 1934, Cook apparently told

Lovecraft that Munn had become “religious,” and it was possibly this that had

led to Munn’s despondency toward publishing as well as ignoring Cook and

Lovecraft. About this, Lovecraft told R. H. Barlow:

Cook says he’s going to get after Munn in person &

give him hell. Munn has a lot of Cook’s property in his custody, & won’t

respond to any enquiries about it. Cook now advances the theory that Munn’s

religious fanaticism is responsible for his boorish silence—that he has wiped

all atheists off his books & won’t have anything to do either with us or

with any interests with which we’re connected. That sounds far-fetched though

to me.[19]

Apparently, Cook was

needing access to the library he, a year earlier, gave Munn, and it was being

denied him for some unknown reason. From this point, Lovecraft became a bit embittered

at Munn and began disparaging him in his letters, calling him the “elusive and invisible

Werewolf of Ponkert,”[20] and “the Werewolf.”[21] In the Autobiographical Writings of R.H. Barlow,

in the section titled, “Memories of Lovecraft 1934,” Barlow recalled, “H.

Warner Munn has such a belief in the supernatural as to have caused him to

become Catholic after his marriage; and almost repudiate his earlier work as

morbid and not nice. Recently he wrote a thing L. [Lovecraft] contemned (“The

Wheel” is an old thing) and said Munn was getting seedy.”[22]

Other than Lovecraft’s

letters, there is no explanation of why Munn was absent from both his friends

and from publishing during this time. It may have been because of religious

commitments, for a time Munn was a council member at Ascension Lutheran Church.[23] However, I have not found

any evidence that he converted to Roman Catholicism at any time in his life

(other than Barlow’s reference to it) It may have been that Munn needed to give

his family more attention. It’s possible it was a combination of

both. Whatever the case, and it is pure speculation at this point until further

information about it surfaces, Munn did not resurface until 1939 when he

submitted his “King of the World’s Edge” series to Weird Tales. Afterward he went back into seclusion, this time probably

actually due to family responsibilities, with two children and a wife to

support (and two more kids born in the 1940s). And, as mentioned earlier, Munn

did not reappear in the publishing industry until the 1960s. Additionally, when

Lovecraft died in March of 1937, Munn was surprisingly quiet about it.

Be that as it may, Lovecraft and Munn were good friends

for many years. And, in the winter of Munn’s life, he wrote a two-part

reminiscence of his old friend for the fanzine Whispers, detailing fond memories he had visiting, traveling, and carrying

on lengthy conversations with Lovecraft. And, even though Lovecraft did

not prefer traditional Gothic stories, he complimented some of these same works and others by Munn to his writing peers. Lovecraft was especially fond of two of Munn’s

earlier works, “The City of Spiders” and “The Chain.” Lovecraft admits to

August Derleth that “‘The Chain’ is certainly his masterpiece to date.”[24] Moreover, “City of

Spiders” was a favorite of Robert E. Howard’s, who admitted so in a 1934 letter

to Lovecraft: “I remember his ‘City of Spiders’ as one of the most striking and

powerful stories I have ever read; and his “Tales of the Werewolf Clan” had the

real historic sweep.”[25]

Regarding

Munn’s story, “The Werewolf of Ponkert,” Lovecraft once confessed in a letter

to Robert Bloch:

I had a letter in the Eyrie in 1923 [the letter was

actually in the March 1924 issue] in which I called for the ghoul’s or

werewolf’s point of view, but nobody seemed to get the point. H. Warner Munn thought he was following out my idea

when he wrote his “Werewolf of Ponkert” (told by a man who was involuntarily

became a werewolf, & who regrets his nocturnal deeds), but in reality he

wholly missed it. His sympathies were still with mankind—whereas I called for sympathies

wholly disassociated from mankind & perhaps violently hostile to it.[27]

It is true, in the March

1924 letter to “The Eyrie,” Lovecraft added the caveat, “. . . and sympathizing

strongly with the devil to whom he has sold himself.”[28] Munn had dropped the ball

on that aspect of Lovecraft’s request, but the readers still got a first-rate

weird horror story with “The Werewolf of Ponkert.” Moreover, since Lovecraft

established the parameters of the requested story, one wonders why he did not

write it himself. “The Outsider” was the closest Lovecraft came to satisfying

that idea. Interestingly, Lovecraft, in that same letter to Bloch, indicated

that Bloch’s story, “Nocturne Macabre”[29] was the first thing he

had read that fit the bill.

[Thanks to Bobby Derie

for fact checking this article and providing a few helpful insights]

Notes:

[2]

Ibid.

[3]

Ibid.

[4] This

is possibly "The Werewolf of St. Bonnot" (WT May-Jun-Jul 1924), but it’s

more likely "The Phantom Farmhouse" (WT Oct 1923).

[5] Wright,

Farnsworth. “The Eyrie.” Editorial. Weird

Tales, August 1925.

[6] Munn,

H. Warner. “HPL.” Whispers, Whole

Number 9, Vol. 3, no. 1 (December 1976): 24.

[7]

Ibid.

[8] Lovecraft, H. P., and Clark Ashton Smith. “1927.”

In Dawnward Spire, Lonely Hill: The

Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, edited by David E.

Schultz and S. T. Joshi, 139. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press, 2017.

[9] Lovecraft,

H. P., and Clark Ashton Smith. “1930.” 220.

[10]

Bobby Derie in personal correspondence, 5/21/2018.

[11]

See Dawnward Spire, Lonely Hill: The

Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, 248.

[12] Lovecraft,

H. P., and Clark Ashton Smith. “1930.” 245.

[13] Lovecraft,

H. P., and August Derleth. "1930." In Essential Solitude: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and August Derleth:

1926-1931, 305. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press, 2013.

[14] Munn,

H. Warner. “HPL: A Reminiscence” Whispers,

Whole Number 13-14, Vol. 4, no. 1-2 (December 1976): 24.

[15]

Ibid.

[16] Lovecraft, H. P., and R. H. Barlow,

"1934." In O Fortunate

Floridian: H. P. Lovecraft's Letters to R. H. Barlow, edited by S. T. Joshi

and David E. Schultz, 54. Tampa, FL: University of Tampa Press, 2016.

[17] W.

Paul Cook to Donald Wandrei, 23 Aug 1931, quoted in W. Paul Cook: The Wandering Life of a Yankee Printer 40. (Donnelly,

Sean (ed.) (2007). W. PAUL COOK: The

Wandering Life of a Yankee Printer. NY: Hippocampus Press)

[18]

Ibid. 105

[19]

Ibid. 155.

[20]

Ibid. 164.

[21]

Ibid. 173.

[22]

Ibid. 404.

[23] See: Reginald, R. Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature. Vol. 2. Detroit MI: Gale

Research Company, 1979. Entry for H. Warner Munn.

[24] Lovecraft,

H. P., and August Derleth. "1932." In Essential Solitude: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and August Derleth:

1932-1937, 475. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press, 2013.

[25] Howard, Robert E., and H. P. Lovecraft.

"1932." In A Means to Freedom:

The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard: 1930-1932, edited by

S. T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, and Rusty Burke, 292. New York, NY: Hippocampus

Press, 2009.

[26]

See Reginald, R. Science Fiction and

Fantasy Literature. Vol. 2. Detroit MI: Gale Research Company, 1979. Entry

for H. Warner Munn.

[27] Lovecraft,

H. P., and Robert Bloch. "Letters to Robert Bloch." In Letters to Robert Bloch and Others,

edited by David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi, 49-50. New York, NY: Hippocampus

Press, 2015.

[28] Lovecraft,

H. P. “The Eyrie.” Editorial. Weird Tales,

March 1924.

[29]

This story no longer exists.

No comments:

Post a Comment