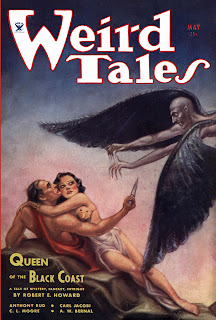

Robert E. Howard’s short story “Queen of the Black Coast”

introduced Conan’s first love, Bêlit, a passionate, ruthless pirate queen full

of “the urge of creation and the urge of death” (128). Her name comes from the

same storehouse of Canaanite/Assyrian legends that brought deities like Ishtar

and Derketo into Howard’s Hyborian Age fiction. In real-life legend, Bêlit belonged

to the same pantheon, often associated with Ishtar and Derketo, although it’s

hard now to know whether the goddesses were popularly connected at the time of

their active worship, or whether the association happened when the sources were

later compiled out of varied lore.

In either case, Howard’s

Bêlit namechecks two goddesses with whom her namesake was syncretized (Ishtar

and Derketo), and also mentions Bel, who was her counterpart’s father in some

legends and her husband in others, saying, “Above all are the gods of the

Shemites – Ishtar and Ashtoreth and Derketo and Adonis. Bel, too, is

Shemitish…” (Howard 247).

The following

tidbits are taken from The Story of

Assyria, by Zénaïde Ragozin, known to

have been one of Howard’s sources:

“As to the female deity of the Canaanites, ASHTORETH (whom the

Greeks have called ASTARTE), she is the ISHTAR and MYLITTA and BÊLIT

(“BAALATH,” “Lady,”) of the Assyro-Babylonian cycle of gods, scarcely changed

either in name or nature; the goddess both of love and war, of incessant

production and laborious motherhood, and of voluptuous, idle enjoyment , the

greatest difference being that Ashtoreth is identified with the moon and wears

the sign of the crescent, while the Babylonian goddess rules he planet Venus,

the Morning and Evening Star of the poets” (107 – 108).

“The planet Venus appearing in the

evening, soon after sunset, and then again in the early morning, just before

dawn, it was called Ishtar at night and Bêlit at dawn, as a small tablet

expressly informs us; a distinction which, apparently confusing, rather tends

to confirm the fundamental identity between the two, -- Ishtar, ‘the goddess,’

and Bêlit, ‘the lady’” (19).

“In ASCALON, where the goddess was worshipped under the name

DERKETO, she was represented under the form of a woman ending, from the hips,

in the body of a fish” (111). This is of particular interest to Howard readers,

since we know that Bêlit’s “fathers were kings of

Askalon!” (Howard 243).

Ragozin also states, “To the

Canaanites, the Sun and Moon – the masculine and feminine principles, as

represented by the elements of fire and moisture, the great Father and Mother

of beings – were husband and wife. … in Ascalon and the other cities of the

Philistine confederation they both assumed the peculiarity noted above,

together with other names, and became, she, the fish-goddess Derketo, and he,

the fish-god Dagon (from dag, fish,

in the Semitic languages)” (114).

Of course,

Derketo is mentioned as a goddess in Howard’s stories; Dagon is well-known, especially

from the work of H.P. Lovecraft, but also appearing, connected with Derketo, in

Howard’s story “The Servants of Bit-Yakin.”