|

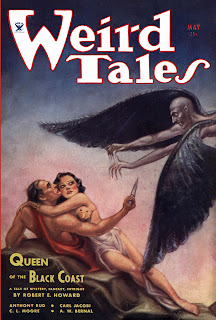

| WT May 1936 |

The strong swordswoman characters created by Robert E. Howard (like Bêlit, Valeria, Dark Agnes, and Red Sonya of Rogatino) garner a lot of attention, and deservedly so. But his work also features a completely different, but equally distinctive, mode of strong female character, as found in his science fiction novel,

Almuric.

The textural history of this novel is complex, as it was unfinished at the time of his death, and first published in 1939. The current available evidence suggests that it was finished by

Weird Tales’ editor Farnsworth Wright, who “pieced together an ending from the first draft and used it to complete the second draft to make a complete story” (quoted by Douglas A. Anderson). In exploring the novel’s characters and their development, it should be kept in mind that certain elements may not have been Howard’s ultimate intent, although, as Anderson points out, “there is no actual evidence that Wright wrote or tampered much with the text.”

Almuric is the tale of Esau Cairn, a man "transported … from his native Earth to a planet in a solar system undreamed of by even the wildest astronomical theorists" (55). He was a man "born outside his epoch," with enormous physical strength, and "impatient of restraint and resentful of authority" (56). Struggling for survival on a bizarrely primitive alien world, full of giant beasts of prey, he finds himself for the first time "alive in every sense of the word," free from "the morbid and intricate complexes and inhibitions which torment the civilized individual" (74).

This story reflects statements Howard made in his letters to H.P. Lovecraft, about the invigorating effect of struggle and labor, and musing on what life would be like for a modern person thrust into a barbaric world. Notably, he says in such a primal, materially-oriented world, he’d prefer to be a true barbarian, "never troubling his head about abstractions, and really living his life to its fullest extent" (507).

Carin falls from this Eden of direct physical experience when he learns there are other people on the world, who seem to speak English. Unexpectedly, "a desire for human companionship" overtakes him (77), and he ventures to a walled city, where he is quickly captured and imprisoned although his strength and endurance will win him a place with the warriors of the tribe. Here he meets Altha, a young woman immediately associated with “some gentle and refined civilization” in the narrator’s mind (82). Previously, Cairn hadn’t seen refined civilization as a good thing, but it seems like a more positive thing when represented by a pretty girl with "lissome limbs" (ibid).

She re-enters the story when he’s held as a prisoner, and speaks in Cairn's defense with a strong sense of justice that is unusual in her society, otherwise so focused on physical might and the struggle for survival. At the idea that they are brutally treating a man who "came alone and with empty hands," she cries out, “It’s beastly!” (89-90)

Beastliness is a significant attribute: a few pages later, Cairn will explain that he came to this city because "I was tired of living among wild beasts" (91). By opposing what's "beastly," Altha is in a sense speaking up for the higher values, including the sense of right and wrong, that separate humanity from animals.

Eventually Cairn's exposition tells us more about the world where Altha has grown up. With their harsh existence, the men are "ape-like" (82), rough and physical, without any “superficial adjuncts of chivalry” (107). The women, however, are sheltered and protected, “carefully guarded and shielded both from danger and from the hard work that is the natural portion of the women of Earthly barbarians” (106). In their intimate relationships, the women are treated with "savage tenderness" by their men, who "assume all authority. The Gura woman has no say whatsoever in the government of the city and tribe … Her scope is narrow; few women ever set foot outside the city in which they are born" (ibid).

Despite their limited, even cloistered existence, Cairn (or the author) stresses that "time does not seem to drag for them. The average woman could not be persuaded to set foot outside the city walls … they are content" (107). Within this society, generally treated like an over-protected child, a woman like Altha can still be whipped until she’s bloody for disobedience, which is mentioned as a possibility (90, 112, 113), an adjunct to the fact that she’s considered more a possession than a human being with moral agency.

As Altha becomes more strongly contrasted to the "average woman" within her society, her story takes on more the nature of an allegory. The primitive peoples of Almuric are contrasted to the "civilized" people of Earth, but at the same time, their everyday unconsciousness evokes the similar complacency of many civilized men and women. Taking their existence and the kind of society they live in for granted, the "average" person isn’t expected to question his or her lot in life.

Before long, Cairn, hunting in the dangerous wilds miles outside the city walls, discovers how strong her difference is from the average woman her society expects her to be, when he finds her running from one of the planet's monstrous birds.

“You are not like the other women,” he tells her. "Folk say you are willful and rebellious without reason. I do not understand you" (111). She ignores this statement, but lets him know that if he brings her back, all she will do is "run away again--and again--and again!" (112). She is compelled to do something which is considered unthinkable among the women of her tribe, but which is a marker of just how discontent she is with her life.

When Cairn points out the danger that "some beast will devour you,” she responds with defiance: "So! … Perhaps it is my wish to be devoured” (ibid).

Since Altha has every privilege in her world, Cairn is puzzled by this, and she responds by posing a philosophical dilemma: “To eat, drink, and sleep is not all … The beasts do that.” And then she explains herself in a powerfully articulate speech: "Life is too hard for me. I do not fit, somehow, as the others do. I bruise myself on the rough edges. I look for something that is not and never was" (ibid).

This statement is again reminiscent of comments in Howard’s letters to Lovecraft, describing how the shaman of a barbaric time would suffer as "a distorted dweller in a half world, part savage and part budding consciousness" (507). This aptly describes Altha’s position as a thoughtful, reasoning person, who is not socialized to the environment of savagery where she has always lived.

When she continues to question. "What constitutes life? … Is the life we live all there is? Is there nothing outside and beyond our material aspirations?" (113), Cairn tells her that on his home world, "there is much grasping and groping for unseen things," adding that "I met many people who were always following some nebulous dream or ideal, but I never observed that they were happy" (ibid).

|

1964 Ace Books Almuric

cover illustration by

Jeff Jones |

As is the situation for people back on planet Earth, Altha's "groping for unseen things" is not something she can truly control, which sets her apart, feeling isolated and alone, as the only one questioning anything within this stagnant society, which has been described as "stationary, neither advancing nor retrogressing" (105). Her interest in the story’s lug of a hero lies in the fact that, like her, he’s different from the average person in her society, and his isolation makes him seem like a kindred spirit.

At this point, Cairn, who is not himself much of a thinker, completely misunderstands her. He thinks she’s looking for “more superficial gentleness,” or conventional chivalry, from him (113). Looking at her through the distorted lens of his own expectations, he deeply misunderstands her perspective. She has been talking seriously about far-reaching, existential concerns – questioning the point of being alive -- and has not suggested anything about a romantic connection between them, much less expressed any desire for him to treat her with “gentleness.” But while Cairn as the narrator is clueless about this, the author who put the words in her mouth clearly isn’t.

In the end, after the two have become as a couple, they work to bring “culture” to the planet (193). It’s possible that this wasn’t the ending Howard envisioned, but as Anderson points out, it does seem fitting for a work influenced by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Working together, Altha and Esau Cairn operate as a synthesis of opposite approaches to life, showing that a society needs places for both the body and the mind. Altha was miserable on Almuric, and Cairn was a freak on Earth, because her world treated the material as all, and his devalued the material too much, but the two complement each other, which could easily have a symbolic meaning.

With her desire for things that never were, the idea of bringing culture to Almuric seems likely to have been Altha’s. Women are often talked about as a civilizing influence on a society, a common trope when talking about, say, the American frontier. Here, that role is taken not by women as a general class, but by one individual woman whose philosophical bent makes her an outsider among her own people, but also makes her a potentially elevating force.

Cairn still attributes this quality to her having "the gentler instincts of an Earthwoman" (193), which doesn't quite describe a girl who'd rather be torn apart by wild animals than live a dull and sheltered life with a narrow scope.

Works Cited

Anderson, Douglas A. “New Evidence on the Posthumous Editing of Robert E. Howard’s ALMURIC.” A Shiver in the Archives. http://ashiverinthearchives.blogspot.com/2016/03/new-evidence-on-posthumous-editing-of.html

Howard, Robert E. Adventures in Science Fantasy. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2012.

Howard, Robert E. and H.P. Lovecraft. A Means to Freedom: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. Two Volumes. Edited by S.T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, and Rusty Burke. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press, 2011.